How to Write a Good Paper

ECON 306 · Microeconomic Analysis · (Last update: Spring 2020)

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/microS20

microS20.classes.ryansafner.com

Most Academic Writing is Terrible

Source: Collegehumor: If Everyone Still Wrote like they did in College

The Purpose of this Guide

To improve your writing, researching, and presentation skills.

To be able to constructively criticize the writing, research, and presentation of others.

- Note: This guide is generic enough (although geared towards "research" papers) to cover most forms of papers, and certainly applies to your assignments

- You will use all of these skills regardless of whether you go into academia, government work, nonprofits, or private industry

Note this is a much more succinct guide than my original. See that for an excessive amount detail and clutter.

The Purpose of a Paper

The Purpose of a Paper

The purpose of any paper is to persuade

Everything else is secondary!

- Inform reader of new information

- Report new finding,

- etc.

Otherwise, why did you write the paper?

Your Goal for the Assignment

Goal is to convince a general reader, NOT your professor

I am NOT your audience! You're not trying to convince me (you might, though)!

You are the lawyer in the courtroom, trying to make an argument to convince a jury of your peers, I am the judge

- I evaluate how well your paper would convince someone else and that you are playing by the rules

The Means

A reader must be convinced through the use of an argument

Arguments use premises and reasoning to support a conclusion

That conclusion is your thesis statement

The Thesis

The Thesis I

Summarize your entire paper's argument in a single sentence (two at most!)

- If you cannot, you do not have a thesis

- Narrow your topic until you can (see section on choosing a topic)

Your paper is NOT "about something"! It should put forth a claim that you attempt to prove or defend

"This paper is about immigration."

"The current immigration policy makes it too difficult for high-skilled immigrants to contribute to our GDP."

"The US should adopt an open borders immigration policy."

"A strong border defense is the most effective deterrent to terrorism."

The Thesis II

- The thesis should be a claim:

1.It should be debatable and relevant

"Murder is bad."

"Capital punishment is the most efficient deterrent for violent crimes."

2. It should be as specific as possible, given the length constraints.

"Intellectual property law is very complicated."

"The problems of modern copyright law today stem from the unintended consequences of the Copyright Act of 1976."

The Thesis II

- The thesis should be a claim:

3. It should, in principle or in practice, be testable.

"Chocolate is better than vanilla."

"Economic recessions are caused by sunspots."

"Democratic governments invest less in long term capital projects than autocratic governments."

4. Again, it should not be just a description of something.

"The tariff history of the United States is long and complex."

"The Smoot-Hawley tariff was one of the leading causes of the Great Depression's severity."

Crafting Arguments

Crafting Arguments

- Provide reasons why your thesis is plausible, some combination of the following techniques:

- Economic Theory: what does theory predict?

- Empirical Evidence: what do the "facts on the ground" show?

- Case Study: one detailed example that proves the rule

- Statistical Analysis: what do data and models suggest?

- Narrative: tell us a story can understand & interpret

"What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence." - Christopher Hitchens

Crafting Arguments (for this Assignment)

Op-eds are not research papers (no bibliography, tables, graphs, etc)

Your argument should be consistent with economic theory (or an explanation of an interesting anomaly)

You should show what is relevant in the real world

Case studies are particularly well-suited for Op-eds

Quick stats and interesting numbers help your argument, but this is not the place for regressions!

Op-eds at the end of the day are all narratives! Persuade your reader why they should support your story

Crafting Arguments: What NOT to do

Do NOT merely provide a section of pros, a section of cons, and then make your mind in the final paragraph

- Every semester I will get papers like these, and they're awful

Don't just tell, show!

- You must demonstrate explicitly how you examined the evidence and reasoned to reach the conclusion. You cannot pull the conclusion out of the air

Better to grapple with different aspects of an issue in different paragraphs than a paragraph(s) of random "Pros" and a paragraph(s) of random "Cons"

Using Economic Theory I

- Adopt a positive means-ends framework

- take goals of policy or agents as given

- critique the means used to achieve the above goals

Example: if you argue for/against the minimum wage: Assume policymakers want to improve income for the poor. Is the minimum wage the best means for achieving that end?

- Nobody cares about how you feel, only what you can defend

- Nobody wants to read about why you think they are a bad person

- Normative claims should be explicit, and backed by theory and evidence

Using Economic Theory II

- Ask (and answer) the following questions (as relevant):

- What is the underlying social problem?

- What are the intended goals of a policy/choice? Who and how is it meant to benefit?

- What are the unintended consequences? Who actually benefits and loses and how?

- How does a policy evolve through time? Does it diverge from original intentions?

- What are the institutions in place, and how do they affect the incentives of each player?

- How do changes in constraints change players' incentives?

- Is this policy robust to knowledge problems and incentive problems?

- What are the relevant, feasible, and comparable alternative solultions that might be chosen? NOT UTOPIA.

- What are the counterfactuals to the observations we see in the world?

Using Economic Theory III

Beware prevalent economic fallacies

The Nirvana Fallacy: the alternative to an imperfect system is NOT a perfect utopia, it is a relevant, feasible, alternative (imperfect) system

The Broken Window Fallacy: people overestimate the visible and intended consequences of a policy and underestimate the unintended and unseen consequences (such as the opportunity cost)!

Empirical Evidence I

Apply your theory and/or model to real world scenarios

What are the actual institutions that affect individual behavior?

- e.g. statutes, laws, local customs, history, religious practices, community norms, shared values, morality

How do the conditions "on the ground" channel economic principles?

- e.g. if they add additional constraints, affect relative prices, distort incentives for certain choices

Test any hypotheses, implications, or predictions from theory

Empirical Evidence II

Good rhetorical devices that can persuade easily:

- Statistics

- Graphs

- Anecdotes and stories

These examples however should logically follow from your theory, your theory should not be created out of these examples!

"Theory without facts is dogma, facts without a theory are blind" - Immanuel Kant

Empirical Evidence: Be Modest with your Claims I

Empirical Evidence: Be Modest with your Claims III

Case Studies I

Case study: a detailed analysis of an example that can provide insight about wider theory

Must be relevant, generalizable, not a freak outlier

Don't "cherry-pick" that parts of examples that support your thesis and ignore parts that contradict it

Case Studies II

- What is the effect of a government banning a product?

Case Studies II

- What is the effect of a government banning a product?

The effects of the Prohibition of alcohol in the U.S. (1920-1933)

| Before 1920 | After 1920 | |

|---|---|---|

| Types of Alchol consumed? | ||

| Quantities consumed? | ||

| How were people exchanging? | ||

| Degree of lawbreaking? |

- Control for other variables that affect difference: Great depression, population increase, Smoot-Hawley Tariff, etc.

Case Studies III

Safner, Ryan, (2016), "The Perils of Copyright Regulation," Review of Austrian Economics 29(2): 121-137

Statistical Analysis I

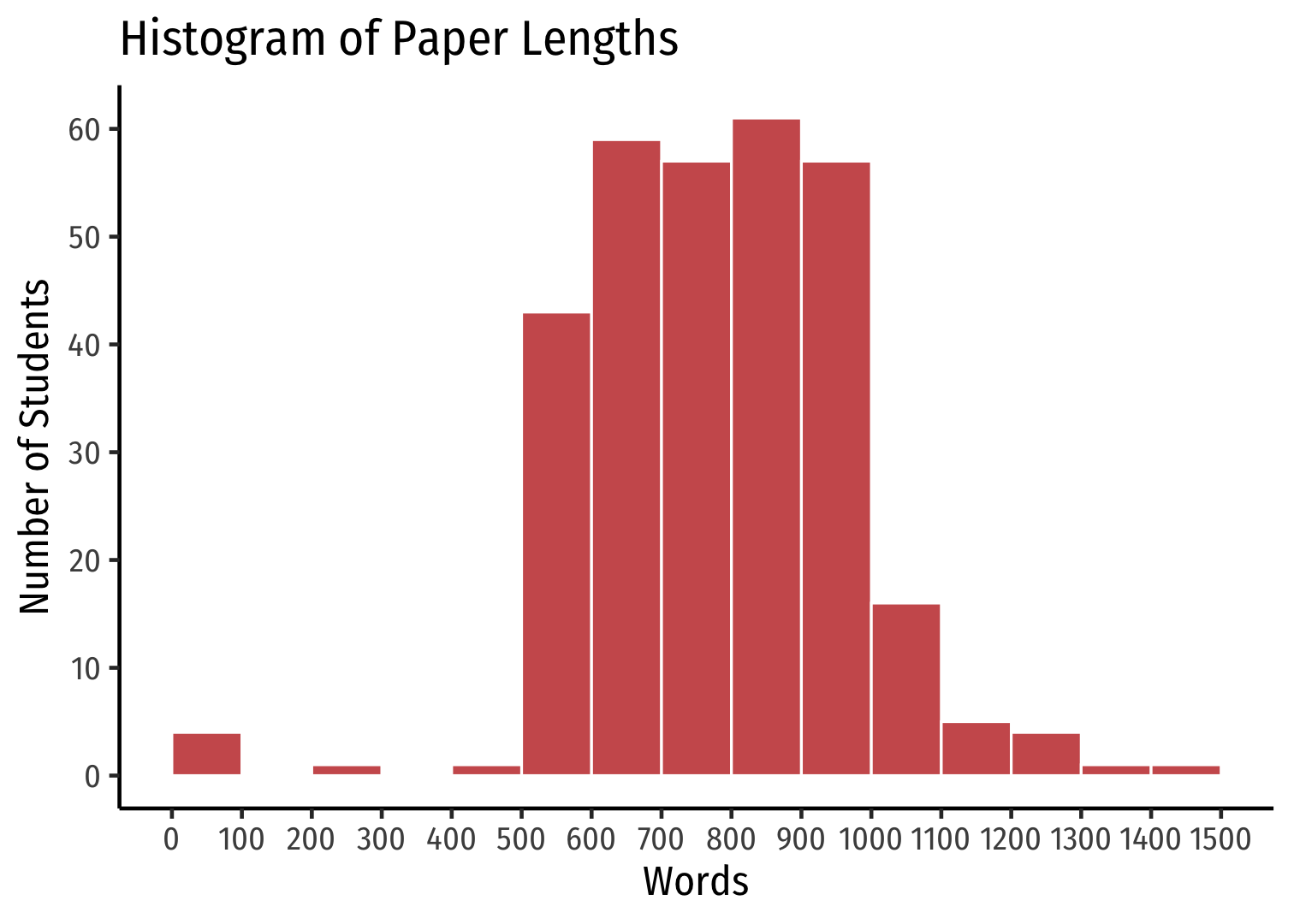

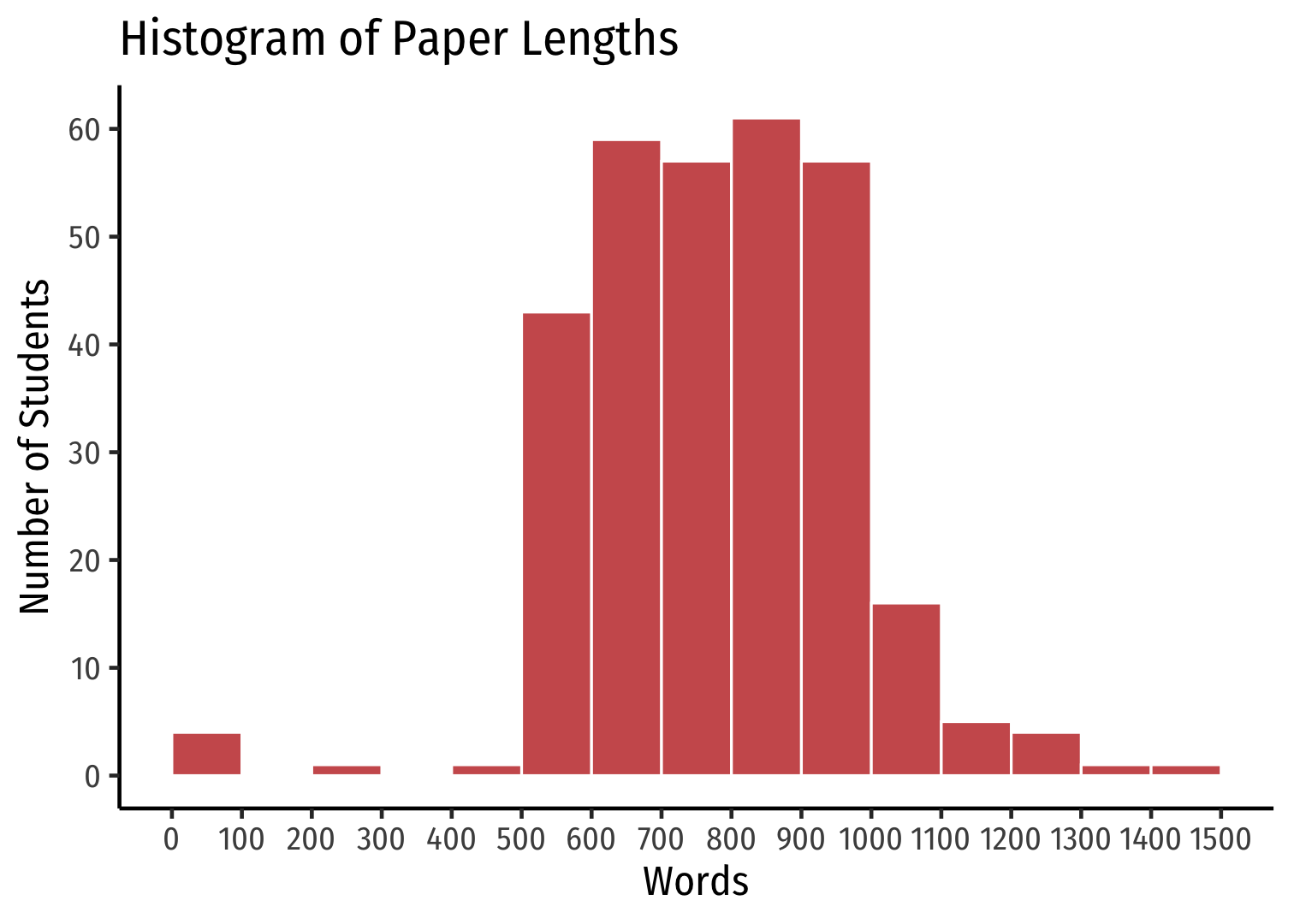

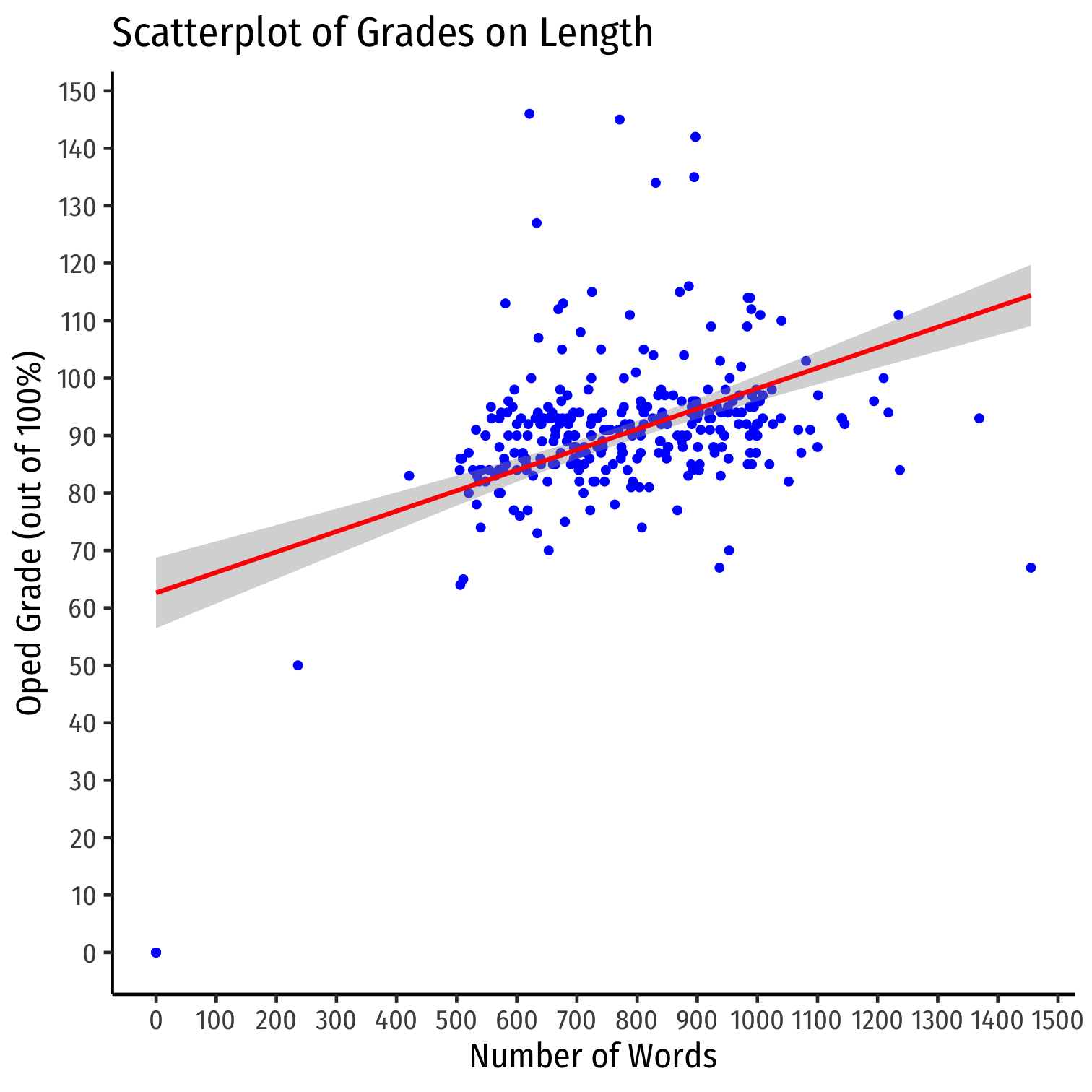

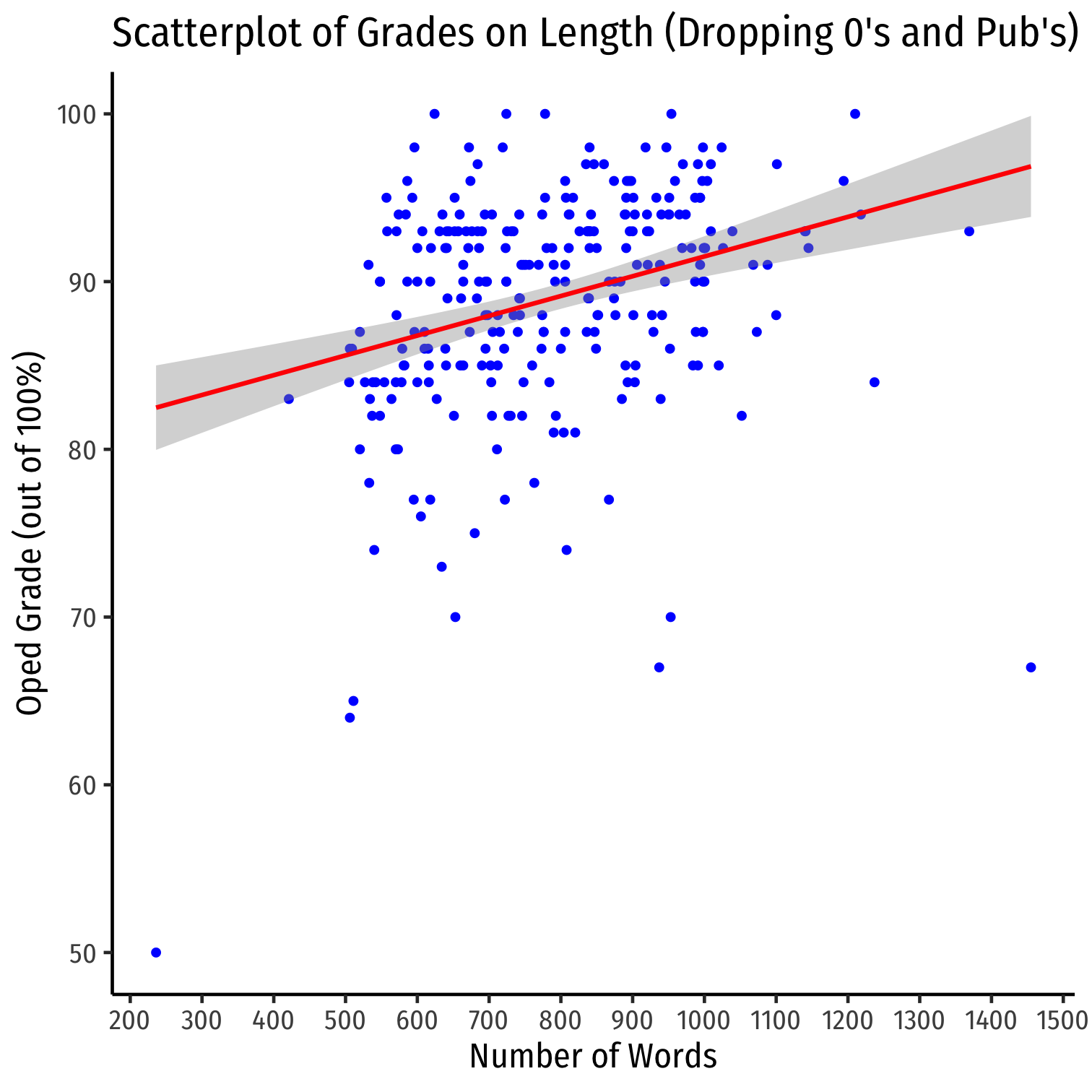

Example: does writing a longer op-ed get you a better grade on the assignment?

Statistical Analysis I

Example: does writing a longer op-ed get you a better grade on the assignment?

Statistical Analysis I

Example: does writing a longer op-ed get you a better grade on the assignment?

| Variable | Obs | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | 310 | 0 | 86 | 91 | 94 | 146 | 90.45 | 14.94 |

| Words | 310 | 0 | 654 | 779 | 915 | 1455 | 782.25 | 194.52 |

Statistical Analysis II

Statistical Analysis III

Statistical Analysis IV

Statistical Analysis IV

Example: does writing a longer op-ed get you a better grade on the assignment?

^Gradei=^β0+^β1Wordsi+ui

| Op-ed Grade | |

|---|---|

| Constant | 62.61 *** |

| (3.13) | |

| Number of Words | 0.04 *** |

| (0.00) | |

| N | 310 |

| R-Squared | 0.21 |

| SER | 13.26 |

| *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05. | |

Statistical Analysis IV

Example: does writing a longer op-ed get you a better grade on the assignment?

^Gradei=^β0+^β1Wordsi+ui

| Op-ed Grade | |

|---|---|

| Constant | 62.61 *** |

| (3.13) | |

| Number of Words | 0.04 *** |

| (0.00) | |

| N | 310 |

| R-Squared | 0.21 |

| SER | 13.26 |

| *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05. | |

What's wrong with this model?

^Gradei=^β0+^β1Wordsi+^β2Qualityi+^β3Topici+⋯+ui

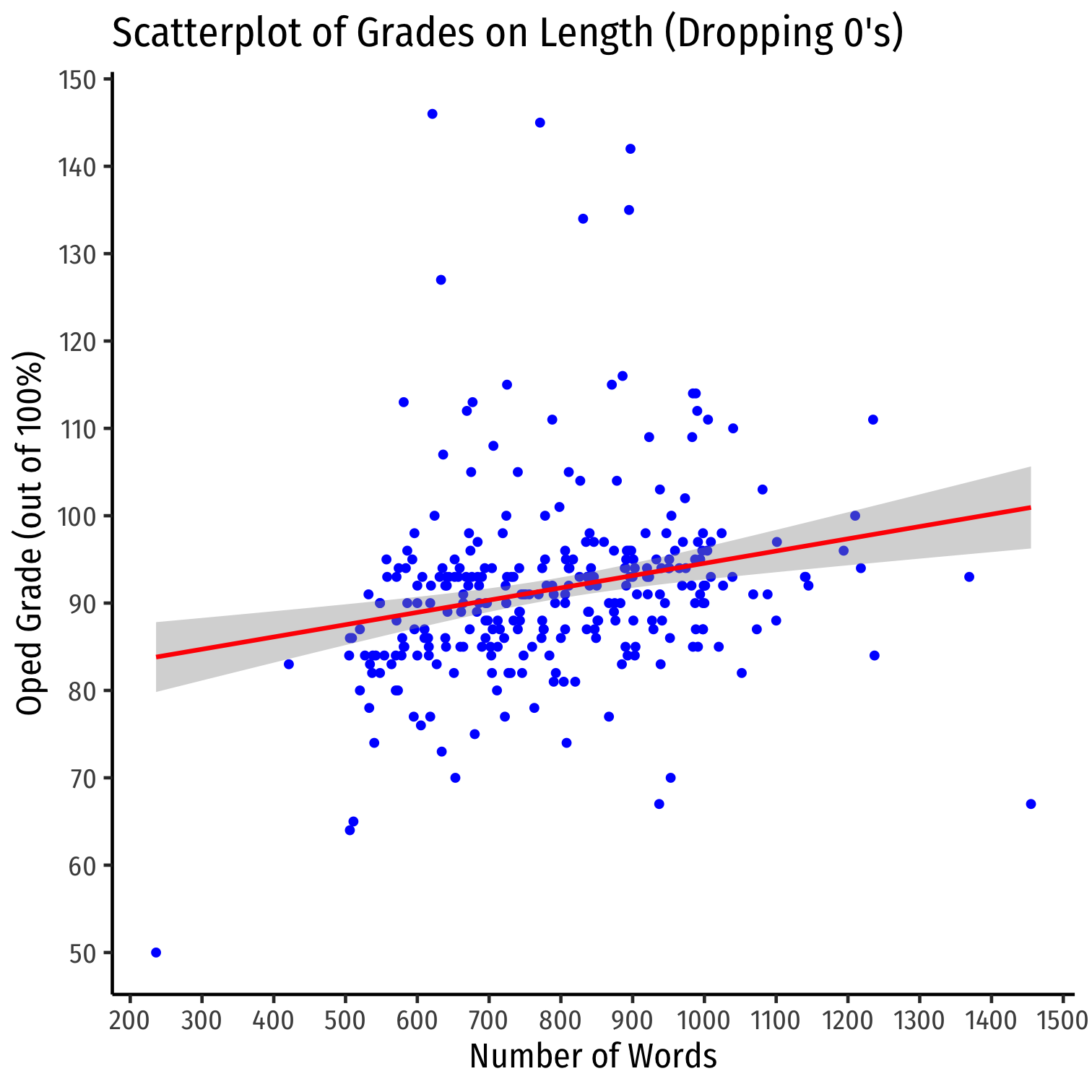

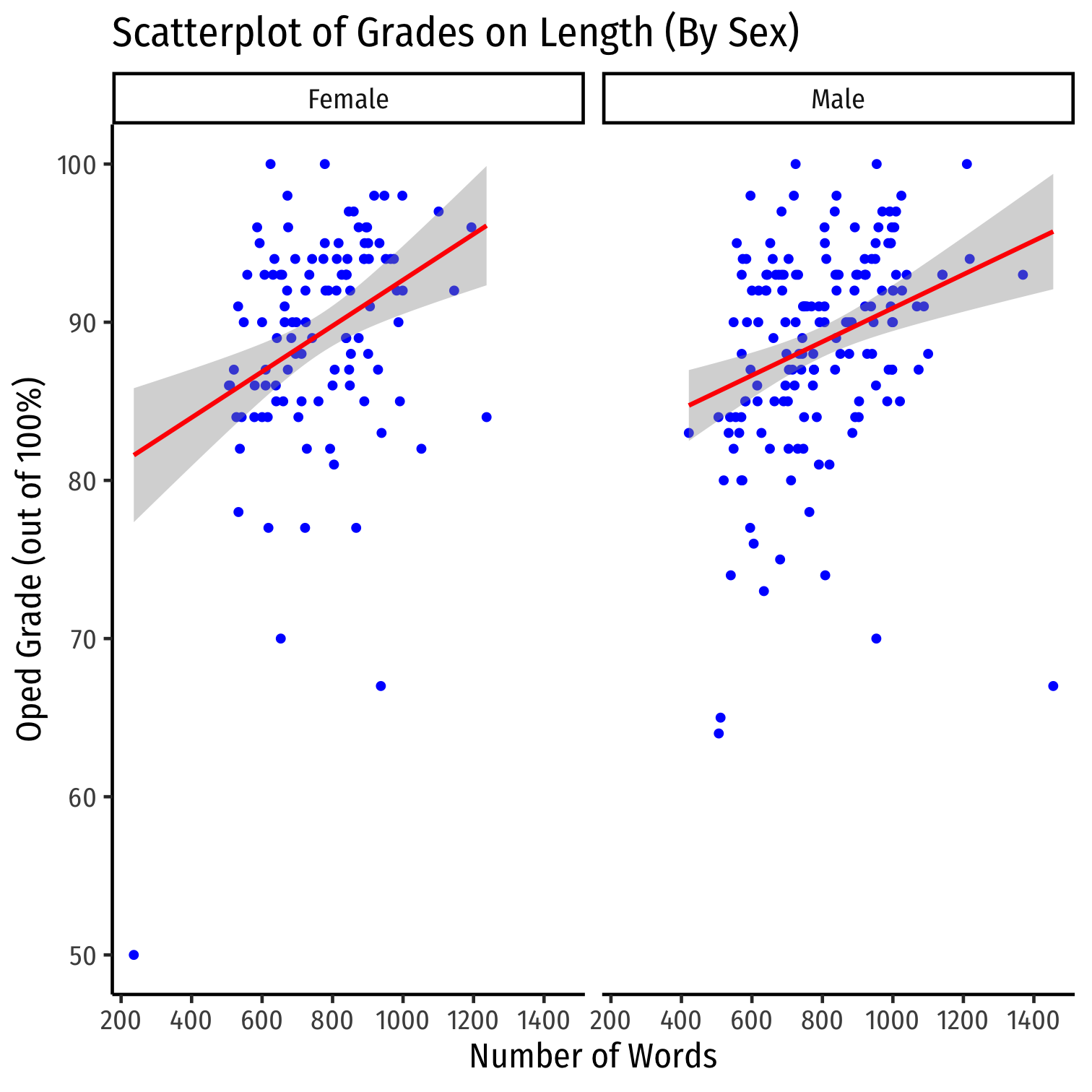

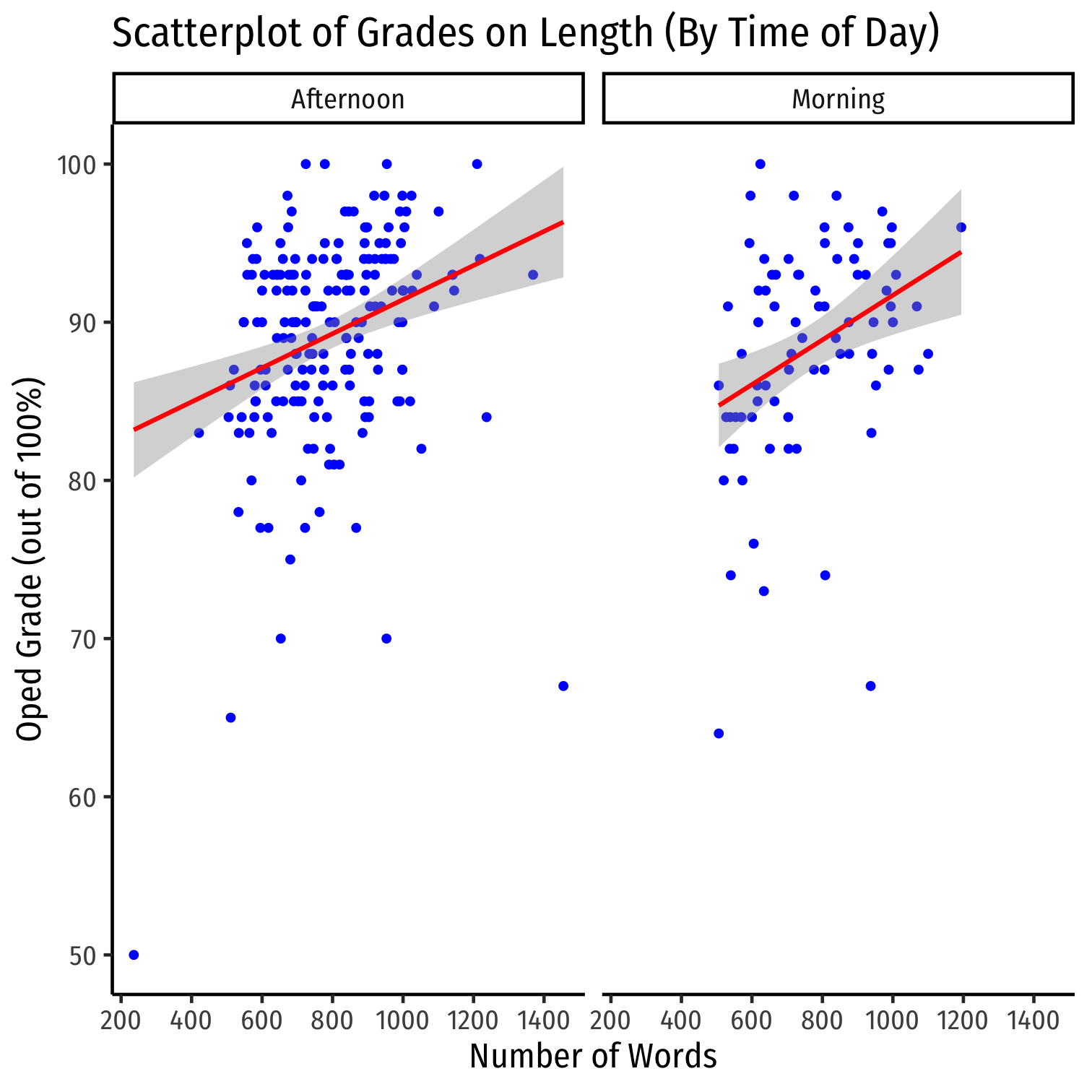

Statistical Analysis V

Statistical Analysis VI

Statistical Analysis VII

| Baseline | Excl. 0's | Excl. 0's and pubs | Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 62.61 *** | 80.50 *** | 79.70 *** | 47.59 *** |

| (3.13) | (2.83) | (1.78) | (3.57) | |

| Number of Words | 0.04 *** | 0.01 *** | 0.01 *** | 0.01 *** |

| (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | (0.00) | |

| Not Hood | 0.41 | |||

| (0.69) | ||||

| Morning | -0.53 | |||

| (0.73) | ||||

| Course Grade | 0.40 *** | |||

| (0.04) | ||||

| Male | -0.57 | |||

| (0.67) | ||||

| N | 310 | 306 | 274 | 274 |

| R-Squared | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.36 |

| SER | 13.26 | 10.58 | 6.41 | 5.42 |

| *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05. | ||||

Narrative

At the end of the day, no matter how technical, mathematical, or scientific, every paper tells a story.

Formulas, tables, and charts are worthless unless we can ascribe meaning to them in the real world. What do those numbers represent?!

Describe, in plain english, the intuition behind your theory, what your observations mean, or how a particular event happened.

Dealing with Alternative Explanations

A good argument recognizes opposing arguments and defends why it is superior, solely on its merits.

Be charitable to people who disagree with you.

- Accept the strongest, most plausible version of your opponents' arguments and argue against these

- Do not take the weast, least reasonable version and argue against that, that is called straw-manning

Recognize that reasonable people disagree for rational reasons - not for irrational reasons (mere opinion, greed, stupidity, evilness, religion, political ideology, etc)

For all honest intellectual arguments, always ask yourself, what evidence, however improbable, would convince me of another view?

See the ideological Turing test idea for more!

Structure of a Paper

Structure of (any) Paper

Introduction

Literature Review

Body

- Theory/Model

- Application/Data/Empirics, as appropriate

Conclusion, Implications

Bibliography

Introduction I

Avoid grandiose statements that wax philosophical.

Economists have long wondered about whether financial markets are efficient. Political philosophers have always sought to discover the origin of political authority.

Get to your thesis ASAP! Consider making it the first sentence

Hook your reader

- Who cares? Why is this important? Why is this relevant? How does this affect people?

- Statistics and background information can often help

- Who cares? Why is this important? Why is this relevant? How does this affect people?

Over 100 million Americans admit to downloading copyrighted material without permission. Under current federal law, that makes one third of the American public felons.

Introduction II

State your thesis as a claim or fact which you will prove and defend.

Briefly outline every major argument you will make in the body, in the order each will appear.

Try to link your key ideas to specific evidence.

Most people do not write enough in their introductions

Consider the incentives of a (skimming) reader pressed for time

- If someone only skims your intro, what do you want them to know??

My rough suggestion: make your introduction about 15-20% of your paper:

| Paper Length | Intro Length |

|---|---|

| 5 pages | 1-1.5 pages |

| 10 pages | 2-2.5 pages |

| 30 pages | 5 pages |

Body

Depends on the topic and the type of data you use

Make sure your arguments flow logically from one to another

- Chronologically?

- General to specific

Consider making each separate argument, sub-argument, and example its own paragraph, section, or sub-section (depending on the paper)

Conclusion

Avoid repeating the introduction. Summarize it in half as many sentences if necessary

- The reader has already read it!

- Most readers skim two sections of a paper, the introduction and the conclusion

Instead, describe several implications of your argument

- what have we learned?

- how can we improve public policy on this issue?

- what more research needs to be done?

Mechanics: Citations, Length & Style

Citations and Quotes

Cite at the end of a quote in the same fashion. Note the punctuation

- e.g. The division of labor is limited by the extent of the market'' (Smith 1776: 87)

- Indent and single-space long quotes (greater than 4-5 lines) to optimize space. Use your own judgment.

A paper that excessively uses long quotations crowds out your own original contributions, and thus, the value (and grade) of your paper will depreciate.

Length

- As long as it needs to be (to do a good job).

"I didn't have time to write a short letter, so I wrote a long one instead." - Mark Twain

- Occam's Razor: Between two competing arguments, the shorter and simpler one is best.

Style

Always tailor it to the specific audience (a journal, the popular media, experts, etc)

At the very least, assume your audience is an educated High School or college graduate with some basic familiarity with your subject area.

- Do not assume they know anything beyond that level

- Do not assume they have taken our class

- So make no references to our class, my lecture notes, class discussions or inside jokes, etc.

Explain all buzzwords, jargon, and concepts they would not be familiar with.

- A brief sentence or two is fine, before moving on to make your actual point

Style (from George Orwell)

Eric Arthur Blair

(George Orwell)

1881-1973

The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one's real and one's declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.

Orwell, George, 1946, "Politics and the English Language"

Style (from George Orwell)

Eric Arthur Blair

(George Orwell)

1881-1973

(i) Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print. (ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do. (iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. (iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active. (v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent. (vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Orwell, George, 1946, "Politics and the English Language"

How to Research

Choosing a Topic

One of the hardest parts of writing a paper is choosing the topic (if you are not prompted with one).

Typical problem: your topic idea is too broad given the length constraints and level of quality expected.

Don't write about something that would take a book(s) to explain!

| Topic | Quality | Optimal Length |

|---|---|---|

| Socialism | Bad | Book(s) |

| The History of the Soviet Union | Bad | Book |

| The Collapse of the Soviet Union | Better | Book/Long Essay |

| The Effects of Perestroika on Soviet citizens | Good | Article |

Choosing a Topic: Search for Puzzles I

Why does something work when we would not expect it to?

e.g. Why and how do pirates cooperate with each other on a pirate ship if they are each murderous, selfish criminals?

Leeson, Peter, (2007), "An-arrgh-chy: The Law and Economics of Pirate Organization," Journal of Political Economy 115(6): 1049-1094

Choosing a Topic: Search for Puzzles II

Why does something not work when we would expect it to?

e.g. Why did FEMA and the Federal Government fail to provide disaster relief after Hurricane Katrina?

Horwitz, Steven, (2007), "Making Hurricane Response More Effective: Lessons from the Private Sector and the Coast Guard during Katrina," Mercatus Policy Series 17

Choosing a Topic: Search for Puzzles III

Are two seemingly-inconsistent facts we observe actually consistent?

e.g. Medieval Europeans used to submerge a suspect's hand in boiling water to determine whether they were innocent or guilty. People are rational.

Leeson, Peter, (2012), "Ordeals," Journal of Law and Economics 55: 691-714.

Choosing a Topic: Passion!

Do not pick a topic only to please someone (unless it's required)

- You will hate the assignment and not write a good paper

Pick a topic you are passionate about, or familiar with, or genuinely curious about

- You will write much better, it will be easier, and you may even enjoy writing it!

Remember, economics is NOT a narrow set of topics (e.g. inflation, stock prices, labor markets), it is a way of thinking about the world

- With a dose of cleverness, you can easily find a way to write about baseball, politics, crowdfunding, pirates, cryptocurrencies, recycling, superheroes, the NFL, video games, contract law, Game of Thrones, the WWE, gender, drugs, sex, rock n roll, etc. (Ask me for examples!)

- Papers out in left field often make for better papers and I want to read these!

Good Writing is Actually Re-writing

Writing is a process, and often collaborative (you need feedback from others to write well)

The more you edit and rewrite, the better your paper will be

The law of conservation of effort: Etotal=Eauthor+Ereader

- The effort your reader must put in is inversely proportional to the amount of effort you put in!

This is why last minute papers are always the worst paper you could possibly write (no time to re-write!)

- Note: A last minute paper might be sufficient for a good grade, but it will be your worst possible writing!

Don't Get Discouraged

Don't Get Discouraged

Don't Get Discouraged

Albert Enstein

(1870-1924)

"If we knew what it was we were looking for, we wouldn't call it research, would we?"